Holocaust memorial ceremony highlights what it means to live after tragedy

The university’s 18th annual Holocaust remembrance. West Haven, April 19, 2022.

At only 10 years old, Eva Cooper was forced to navigate life with her family during the Holocaust. She was instructed to seek signs of her late grandmother, who passed away in the U.S. prior to the war.

“She was my guardian angel and every time we saw a butterfly, my mother would assure me everything was fine,” said the university’s keynote speaker during the 18th Holocaust memorial ceremony last Tuesday.

She stood before the crowd of university community members and told her story, from start to finish, of being a child thrown into the tragedy of the Holocaust in Hungary. “We were being lined up to be shot, which was not a very happy experience… [we] didn’t see any butterflies that day.”

In quoting Holocaust writer Elie Weisel, Lauren Kempton, sociology and psychology professor, said, “Just as memory preserves the past, so does it ensure a future and our dedications to good.”

She commended keynote speaker Cooper, following her anecdotal accounts of living through the tragedies of these warring years, saying “We just heard an amazing memory, and we must dedicate ourselves to keep telling that story.”

The majority of the gathering, which took place in Bucknall Theater, was dedicated to Cooper’s anecdotal retelling. She spoke to the audience about the experiences she endured, including what shaped her identity during her developmental years.

Cooper recalled her tenth birthday party, when she was left to watch her hometown, Budapest, be invaded by German forces from the window. She recalled the prominent memories of the incident, saying, “all of a sudden, the noise became louder and louder.”

Cooper also spoke about the financial struggles of trying to maintain afloat while on the road for safety. She said that as a child, she was left to work with others in order to scrape up money by selling collected newspapers. She also recounted the process of making and selling cigarettes through taking ones tossed to the road, rerolling the remaining tobacco in toilet paper and reselling them.

The rest of the ceremony used a diverse array of mediums to honor the lives impacted by the genocide.

The afternoon began with a candle lighting ceremony, in which eight candles were lit by students (Racehl Blumenthal, Shoshanna Dansiger, Jasmin Garcia, Jordan Glassman, Mark Harvan, Lauren Kachmarsky, Anthony Periera and Josh Zweibel) in the theater. Six candles each represented one million Jewish lives lost due to Nazi forces. One for other groups suffering casulaties, from the gay community to people with disabilities, and the final stood for those who dedicated efforts to aiding those targeting during the Holocaust.

In her opening words, Provost Danielle Wozniak informed the audience of the root meaing of the word Holocaust: sacrifice by fire. She continued in saying, “Like all fire, the Holocuast burned, wherever the triad of hatred power and indifference to suffering convened within Nazi territory.”

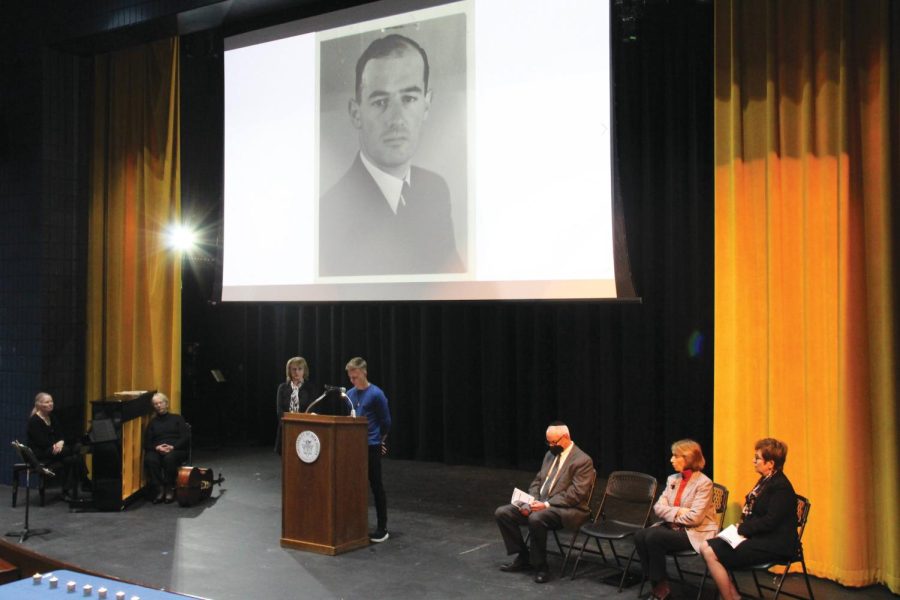

A collection of professors, administrators and university community members lined at the front of the room to read off the names of every life lost during the Holocaust that held a connection to someone within the University of New Haven community.

The memorial ceremony also integrated a number of videos into the afternoon, from sand art created by Israeli artist Ilana Yahav, which depicted a raw retelling of the Jewish perspective of the Holocaust in sand, to a brief documentary following Cooper’s own family members, part of few who escaped the deportation which was the reality for almost half a million other Hungarian Jews. This worked in conjunction with a condensed lecture on the efforts of those seeking to protect the Jewish, with emphasis placed on Raoul Wallenberg, who inspired many to follow him in providing more safe houses and creating protective passports.

Following a moment of silence, Rabbi Richard Eisenberg led a chanting of a Hebrew memorial prayer, which was “adapted to recluse the 6 million who perished.”

As Cooper said, learning the stories of the Holocaust and progressing into life following such knowledge, one can “see what you can do to end this horrific world.”

Emphasis throughout the ceremony reverted back to Elie Weisel’s indication that “to listen to a witness is to become a witness,” and a synthesis of both firsthand memories and secondhand accounts of Holocaust experiences provided an array of content to progress community understanding of the genocide.

Mia Adduci is a senior studying communication concentrating in multi-platform journalism and media who began writing for the paper her first semester on...