A discussion on sex trafficking in the OnlyFans era

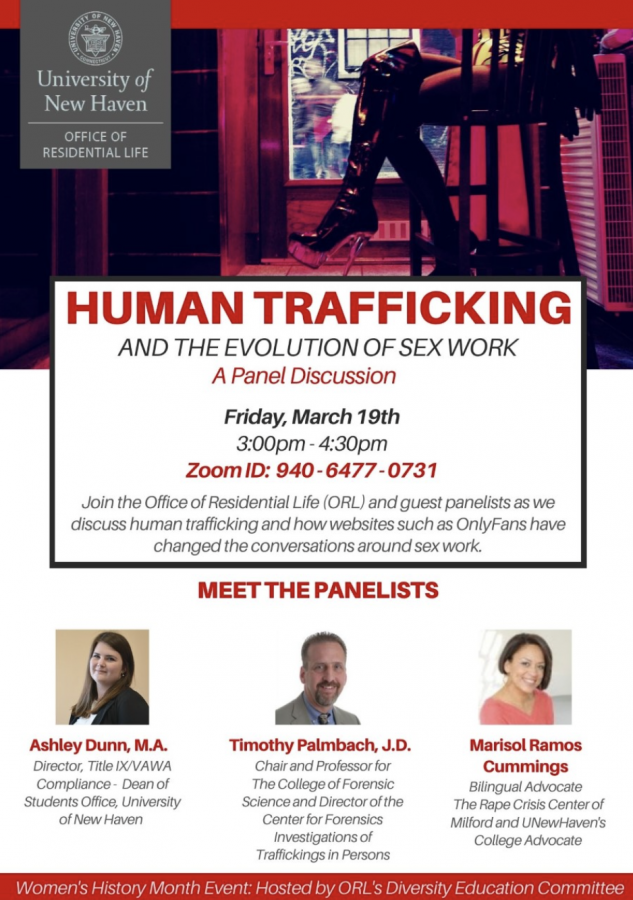

On March 19, the Office of Residential Life (ORL) hosted a panel on “Human Trafficking and the Evolution of Sex Work” via Zoom in honor of National Women’s History Month throughout March and on the cusp of Sexual Assault Awareness Month to be observed in April.

The panelist discussed how new technology and apps, such as OnlyFans, have shifted the stigma and dangers of sex work as it relates to human trafficking. ORL area coordinator Will Frazier and senior forensic biology student and resident assistant Jennifer Edwards moderated the event. Panelists included Title IX/VAWA Compliance Director for the Dean of Students Office Ashely Dunn, director of the Center for Forensics Investigations of Trafficking in Persons and Chair of the Forensic Science Department. Timothy Palmbach, and bilingual advocate at the Rape Crisis Center of Milford, and the university’s college advocate Marisol Ramos Cummings.

The panel opened the discussion by discussing demographics who are most vulnerable to sex trafficking, such as those who experience mental illness, poverty and homelessness. The common factor in all vulnerable populations is a sense of desperation and a level of naivety. According to Dunn, transgender women of color and LGBTQ+ homeless youths are trafficked and exploited at higher rates than most other demographics.

The panelists said that platforms such as OnlyFans present increased opportunities for exploitation, especially after the financial need created by job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. While many of the sex workers are adults and voluntarily in the field, lack of regulation from the app, according to Palmbach, has caused an increase in exploitation, specifically of children. He said that OnlyFans asks creators for their age upon making an account, but does not ask for verification until it is time for creators to accept payment, in which the app then asks for an ID.

“It’s like hiding people in a million little boxes with no keys,” said Palmbach about the ease by which people can be trafficked online and how difficult it is to intervene. He said that apps like OnlyFans market to children on popular social media platforms, like Tik Tok, and that exploitation often continues as their content may be shared and sold to a third-party source.

Dunn and Cummings expressed their assent and expanded upon the lack of regulations. Many of these platforms ask for age verification, not to protect their users, but to protect themselves. This has resulted in a push for additional oversight by non-profits such as the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE), which cites Onlyfans as one of 12 companies who most profit from sexual exploitation on their “Dirty Dozen” list released in February. Onlyfans was joined by Netflix, Reddit and Amazon, among others.

A section of the discussion was centered around defining victimization in order to protect people. Many individuals do not see themselves as victims of sexual crimes until they are able to reflect on their experiences. While consensual sex work exists, Dunn explained that there is a “fine line” and consensual sex work can be easily manipulated to be exploitative. This “fine line” is partially what legislation must work to protect people from as sex workers campaign to decriminalize the industry.

Legislation has been passed to try to protect these individuals from exploitation; however, it commonly backfires and causes more harm to those it aims to protect. In some states, part of the sentence for being caught in sex work is to be placed on the sex offender registry along with perpetrators of sexual assaults. Other legislation completely leaves out protections for demographics such as undocumented individuals, who face deportation if they report exploitation or assault.

Cummings punctuated the juxtapositions in legislation in policy saying, “Who are we? Are we going to let sexual assault happen? Or are we going to condemn them?… Abuse is abuse and everyone needs to be respected.”

While the panelists explained that there are many holes in legislation to be filled, they also provided some actionable ways people can intervene if they suspect sex trafficking is occurring. First, people can look for the signs of trafficking, such as a change in behavior, a new and overly controlling person in the victim’s life, sudden access to money and branding, such as tattoos. They can try to intervene early before the person is isolated by the perpetrator; if the person is isolated, the best course of action is to contact the authorities or health professionals.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual assault or trafficking and wants to speak with someone, you can reach the university’s campus advocate at [email protected], 203-305-1759 or contact the national human trafficking hotline at 1-888-373-7888. You can also file a crime report to the University Police Department on the university Report It! website.

Beth Beaudry is a senior majoring in communication with a double concentration in journalism and public relations, and a minor in English. This is her...

Isabelle Hajek is a senior at the University of New Haven majoring in psychology with a concentration in forensics and a double minor in criminal justice...