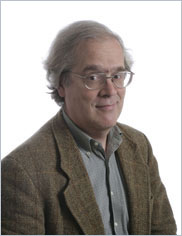

UNH Philosophy Professor David Brubaker was in China this October to speak at two events celebrating Chinese art. The first event was the Songzhuang Art Festival Academic Forum, which took place

Oct. 14 to 18 on the outskirts of Beijing where the city abuts the countryside. Brubaker was slated to share his impressions of an exhibition of works by 10 Chinese artists wrestling with accelerating societal changes. The show, called “Nomadic Reality,” ran both in Beijing and at the Artgate Gallery in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, NY.

The second event Brubaker will attend honors the thirtieth anniversary of the China National Academy of Painting in Beijing. He will be part of an international art forum on Oct. 30 called “Contemporary Art: Globalization and Tradition.” He was invited to the academy because of an essay on the centuries-old practice of literati painting he penned for a book that came out in March titled Subversive Strategies in Contemporary Chinese Art. His essay is being translated into Chinese for the celebration.

Brubaker has been to China three times before. The last time was in August 2010, when he gave a talk on a shorter version of his literati painting essay at the eighteenth International Congress of Aesthetics in Beijing.

The two institutions he is visiting represent differing aspects of the Chinese art community, according to Brubaker. One is a group focused on cutting-edge contemporary art, based in an area “sprinkled with farmers;” the other is in the city and primarily concerned with traditional painting. China’s sweeping growth over the past decade features prominently in the Songzhuang artists’ work. “All these changes are happening within one person’s lifetime. That can be challenging,” Brubaker said, adding that the group has already had to relocate twice because of Beijing’s encroachment.

Two photographs in the exhibition by artist Xu Chanchang, for example, challenge notions of permanence and dispensability. They depict famous works of art, crumpled and unfolded again. Representing China and the East is Dong Xiwen’s “Grand Founding Ceremony of P.R.C.” The West is represented by Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa.” Brubaker pointed out that many Chinese are just beginning to feel the kinds of massive social and environmental shifts that have been themes in North America and Europe for over a century. There are terrible, weird, and wonderful things happening, he said. “It’s also a fascinating chance for conversation.”

By contrast, Brubaker’s visit to the academy will focus more on what Chinese culture can offer the West. His essay on literati painting explored one piece of that question. It investigates five features of the practice of literati painting that help illustrate the Chinese notion that “aesthetic appreciation stems from contact with a place or location in which self is inseparable from natural environment.”

Brubaker views his interaction with Chinese culture as a learning experience. “Many of these works are just being translated. It’s a real opportunity to go back and see what can be extracted for us today,” he said. “The question is whether we can find certain gaps that Chinese culture can fill. The answer, I think, is ‘yes.’”

Before he had a PhD in philosophy and taught it at UNH, Brubaker studied art, earning his MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1980. His interest in art has not waned in the intervening years, and many of his publications combine both disciplines. “I feel like I’m representing the school and community. I see myself as bringing back and sharing my experiences there,” Brubaker said.