From The Associated Press

WASHINGTON – In what may be the scariest shower news since Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” a study says showerheads can harbor tiny bacteria that come spraying into your face when you wash. People with normal immune systems have little to fear, but these microbes could be a concern for folks with cystic fibrosis or AIDS, people who are undergoing cancer treatment or those who have had a recent organ transplant.

Researchers at the University of Colorado tested 45 showers in five states as part of a larger study of the microbiology of air and water in homes, schools and public buildings. They report their shower findings in Tuesday’s edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In general, is it dangerous to take showers? “Probably not, if your immune system is not compromised in some way,” lead author Norman R. Pace says. “But it’s like anything else — there is a risk associated with it.”

The researchers offer suggestions for the wary, such as getting all-metal showerheads, which microbes have a harder time clinging to.

Still, showerheads are full of nooks and crannies, making them hard to clean, the researchers note, and the microbes come back even after treatment with bleach.

People who have filtered showerheads could replace the filter weekly, added co-author Laura K. Baumgartner. And, she said, baths don’t splash microbes into the air as much as showers, which blast them into easily inhaled aerosol form.

It doesn’t seem as frightening as the famous murder-in-the-shower scene in Hitchcock’s classic 1960 movie. But it’s something to be reckoned with all the same.

The bugs in question are Mycobacterium avium, which have been linked to lung disease in some people.

Indeed, studies by the National Jewish Hospital in Denver suggest increases in pulmonary infections in the United States in recent decades from species like M. avium may be linked to people taking more showers and fewer baths, according to Pace.

Symptoms of infection can include tiredness, a persistent, dry cough, shortness of breath, weakness and “generally feeling bad,” he said.

Showerheads were sampled at houses, apartment buildings and public places in New York, Illinois, Colorado, Tennessee and North Dakota.

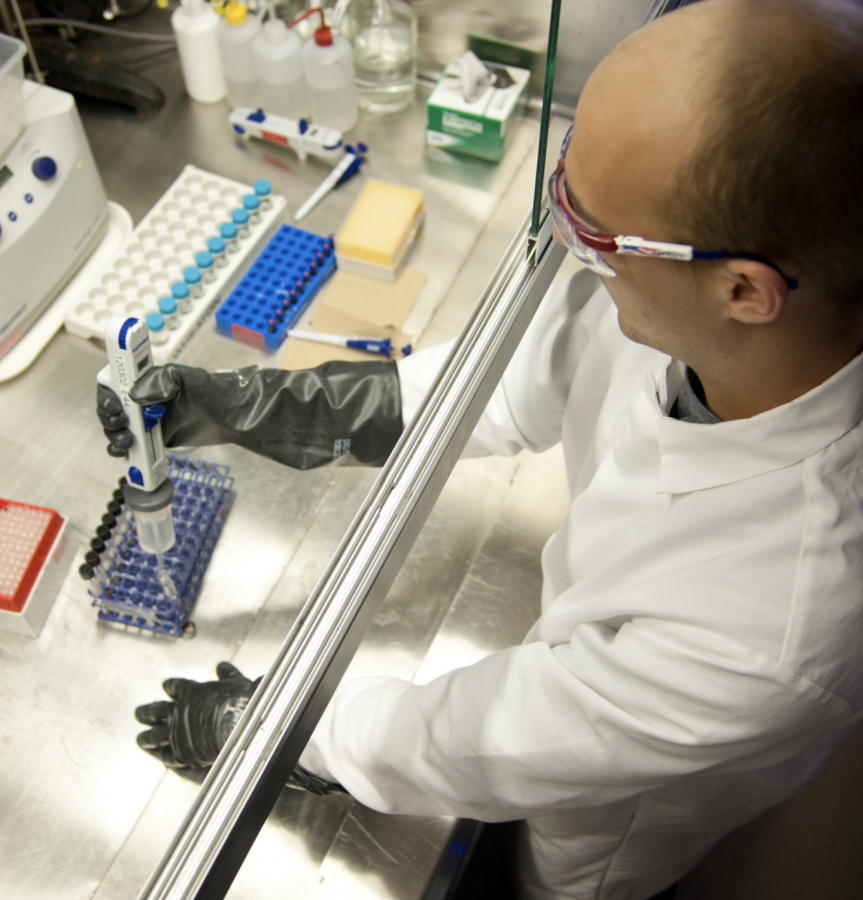

The researchers sampled water flowing from the showerheads, then removed them, swabbed the interiors of the devices and separately sampled water flowing from the pipes without the showerheads.

By studying the DNA of the samples they were able to determine which bacteria were present.

They found that the bacteria tended to build up in the showerhead, where they were much more common than in the incoming feed water.

Most of the water samples came from municipal water systems in cities such as New York and Denver, but the team also looked at showerheads in four rural homes supplied by private wells. No M. avium were found in those showerheads, though some other bacteria were.

In previous work, the same research team has found M. avium in soap scum on vinyl shower curtains and above the water surface of warm therapy pools.

And stay tuned. Other studies under way by Pace’s team include analyses of air in New York subways, hospital waiting rooms, office buildings and homeless shelters.

The research was funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health.

Virginia Tech microbiologist Joseph O. Falkinham welcomed the findings, saying M. avium can be a danger because in a shower “the organism is aerosolized where you can inhale it.”

In addition to people with weakened immune systems, Falkinham also cited studies showing increased M. avium infections in slender, elderly people who have a single gene for cystic fibrosis, but not the disease itself.

Two copies of the gene are needed to get cystic fibrosis, but having just one copy may result in increased vulnerability to M. avium infection as people age, said Falkinham, who was not part of Pace’s