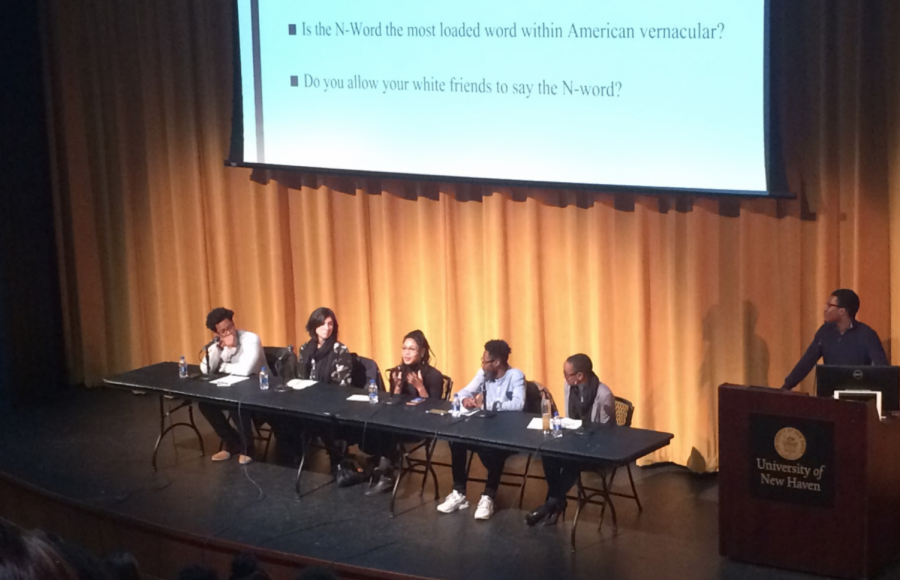

NAACP Hosts N-Word Panel

The University of New Haven’s chapter of the NAACP hosted their annual n-word panel on Tuesday, Nov. 27. The panel was created to discuss the word, as well as to show students the history of the word, how it is used in popular media, and how students of color, particularly black students, feel about the words use.

Panelists included director of NAACP youth and college division, Tiffany Dena Loftin, former president of University of New Haven’s Black Student Union, Marc Wong, former president of the university’s chapter of NAACP, Esperanza Humphrey, criminal justice professor, Dr. Tracy Tamborra, and assistant music professor, Dr. Patrick Rivers. The panel was moderated by university NAACP’s first vice president, Jordan Harris.

The panel opened with Harris asking panelists if they could recall the first time they heard the n-word.

“I was at a private school called the Little Red Schoolhouse in Los Angeles, California, Hollywood, and this white girl named Elizabeth called me the n-word during recess,” said Loftin. “I took her by the hair and slammed her into a tree. True story.”

Later, some debate came up between panelists as they discussed whether they allowed their white friends to say the n-word around them.

“I grew up in Brooklyn and, for me, there are some white people that I would allow, because they grew up in the community around me,” said Wong, defending circumstantial instances of white people saying the word. “There are some white people who get chased by the cops and get treated the same way because they live with us.”

“If I have a friendship with you, that means we’re both woke. And why do you want to use the word?” said Humphrey in opposition. “I’m very hopeful that they learn about the meaning of the word, the history of the word, or that they understand the impact, or that I don’t use it. If I can refrain from using it then, trust me, you can refrain from using it.”

The n-word came from “niger” (NEE-sha) the Latin word for “black,” and was mispronounced by white American southerners. Then, as Dr. Rivers pointed out, the word became an economic term in the 1800s to establish black people as property.

The panel was open to the audience, and several people took to the mic to talk about their experiences either with the n-word or as a person of color in the United States.

“This right here, is not just about the n-word,” said Loftin. “This is about power, and this is about racism, and this is about supremacy, and it’s not just America. It’s international.”

Everett Bishop is a senior at the University of New Haven and is student life editor for The Charger Bulletin. He is double majoring in communications...