Mental health in the wake of COVID-19

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, discussions of physical health have taken precedence over mental health, and as National Suicide Prevention and Awareness Month begins, this disparity is being noticed. As the government temporarily shut down businesses, created isolation guidelines, and has enforced mask mandates, unintended mental health side effects may have developed.

Life stress theory dictates that certain events and situations a person is exposed to can affect their mental state and behaviors. In a 2019 article from the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, it was hypothesized that loss, physical danger, role change/disruption, and difficult to escape situations, are indicators of increased suicidal thoughts or actions. Much of the literature on depression and suicidal thoughts corroborates this hypothesis.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created such life stress; namely great life change and the threat of physical danger. Not only have people had to adapt to lifestyle changes, such as wearing masks, but people have had to reimagine their finances and the new levels of risk associated with ordinary tasks and activities.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 31.3 million individuals in the U.S. reported that they were unable to work due to the pandemic. This statistic does not include individuals who had to make the choice to stop working because of their own or a family member’s preexisting condition.

As of Sept. 23, approximately 200,000 COVID-19 cases have been reported in the U.S. and nearly one million worldwide. Respectively, the infection rates are 36 times and 32 times greater than the death tolls. Telling of the danger of COVID-19, such rates have been a major source of anxiety and stress.

Experts are drawing parallels between the possible mental effects of COVID-19 and other outbreaks. Going as far back as the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu, literature shows that suicide rates mirror infection rates. As infection rates increase, so do suicide attempts. After the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, suicide, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and depression rates also increased. Similar findings were found in individuals impacted by the Ebola virus in 2017.

With these shocking trends, people are asking what they can do to combat the negative mental effects of COVID-19. In July, the Center for Disease Control published a statement on how to cope with various stressors related to COVID-19. Among other private health groups, the New Direction Behavioral Health group recently published a fact sheet titled, “Social Distancing, Quarantine & Isolation: How to Cope.”

Both sources highlight the importance of community and compassion in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to stay connected to those you care about and pay attention to each other’s behavior. Symptoms such as feelings of hopelessness, becoming withdrawn from loved ones, trouble sleeping, and loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities are all symptoms of depression. Hypervigilance and trouble sleeping are indicative of anxiety disorders.

Aside from a lack of resources, the biggest barrier in improving mental health is the stigma associated with diagnosis and treatment. If you or someone you know is experiencing these or other symptoms, be sure to be there for them and provide them with resources for self-care and treatment. More than anything it is important that you show compassion.

One community that experienced unprecedented life changes as a direct result of the pandemic are college students. As many students were sent home early last spring semester and are facing drastically different fall semesters, colleges are focusing on how to support not only their physical health but their mental health as well.

According to the American Council on Education, eight out of 10 university presidents they interviewed perceive mental health as a growing concern on their campus and over one-third of presidents intend on investing more into student mental health initiatives.

These initiatives may include changes in class structures to quell fears related to COVID-19, accommodations made in grading and attendance policy, and increased mental health resources.

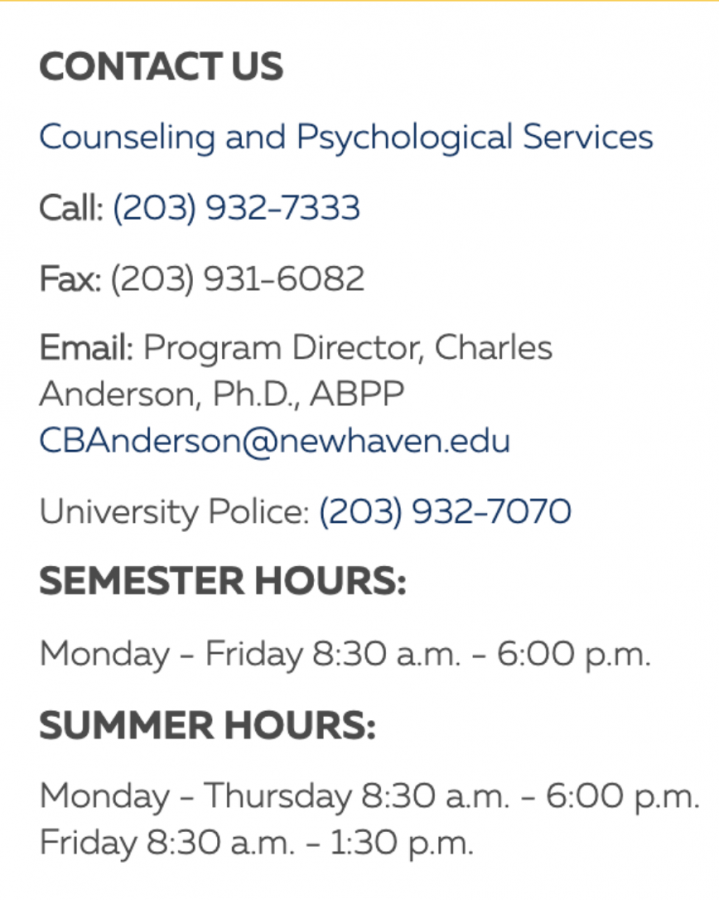

At the University of New Haven, Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) has implemented a “COVID Adjustment” support group, among others. They are asking that those interested contact aaudette@newhaven.edu.

The university has adopted various forms of online and hybrid classes to accommodate students’ anxieties related to exposure to COVID-19. The COVID-19 Emergency Academic Policy Changes have also been extended through the fall 2020 semester. These changes include allowing for pass/fail designation to courses and extended class withdrawal deadlines.

Despite the changes and initiatives, the university has provided, there is still reason for concern regarding mental health. College creates a unique environment for various life stressors to occur during a period of development. This increases the vulnerability of students’ mental health during the pandemic.

For information and help regarding emotional distress and suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 800-273-8255.

Isabelle Hajek is a senior at the University of New Haven majoring in psychology with a concentration in forensics and a double minor in criminal justice...