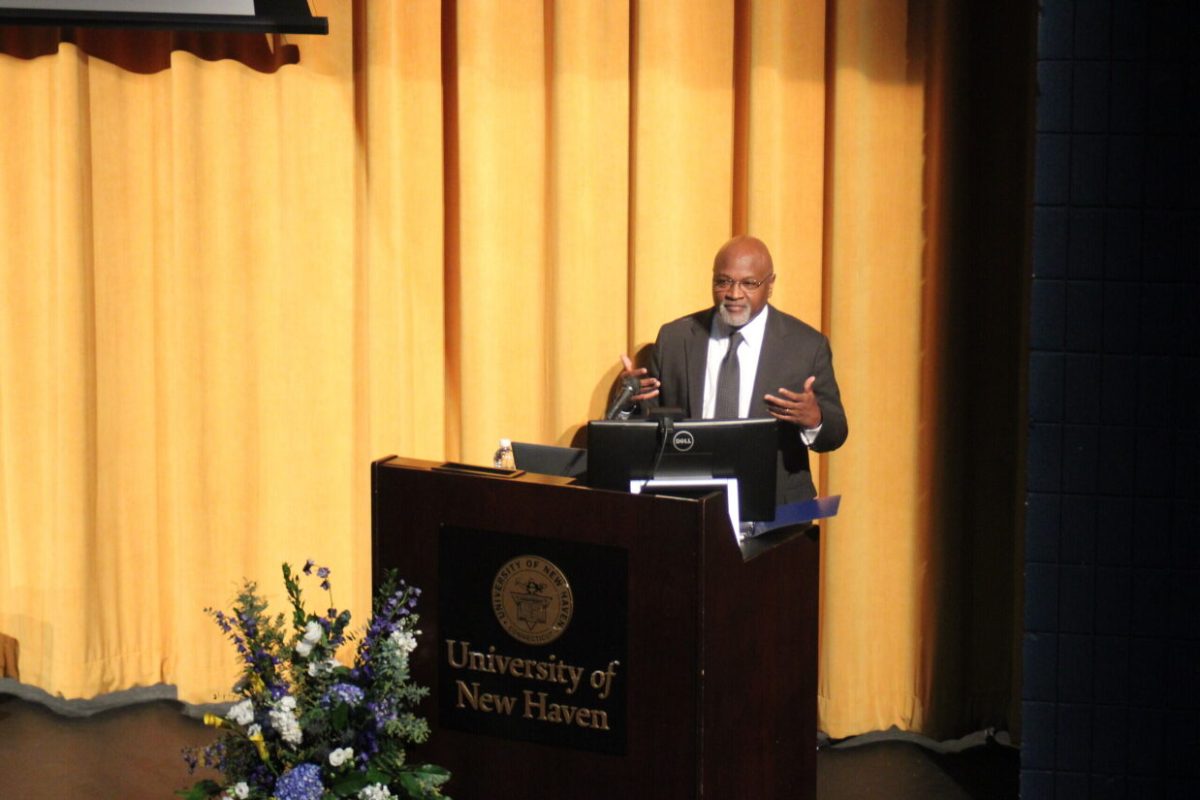

Bias is a growing issue in the legal system, Conn. Supreme Court Chief Justice Richard A. Robinson said last week to a packed Bucknall Theater.

In fact, Robinson said the initial impression and implicit bias of a plaintiff in the courtroom is “one of the most critical points in the process” of seeking to serve justice.

Robinson worked in lower courts across the state until he was appointed to the appellate court in 2007 and eventually became a justice on the state Supreme Court in 2013. He was named chief justice in 2018, the first Black person in the position.

At the midpoint of his presentation, Robinson formally defined bias as “the human trait resulting in our tendency and need to classify things,” though throughout earlier parts of his speech Robinson worked toward building to this definition through illustration.

Robinson alluded to the words of his close colleague Steven Gonzalez, chief justice of the Supreme Court of Washington state, who said that “just because something has been politicized does not mean it is political.”

Robinson talked about the power of socio-political events to shift the conversation around bias and said that 25 State Supreme Courts (or their Chief Justices) “publicly said – for the first time that I know about – that there is a problem with our judicial system” following the death of George Floyd in 2020.

In a poll taken among people who attended Robinson’s speech, 66% said that justice should be blind and 34% said it should not.

Robinson presented photos and descriptions of people and the audience was asked to make judgments. He also spoke about the ways people classified nonhuman entities, like visual images or shapes.

Robinson also highlighted the five building blocks of “fairness” which people expect — fair decisions and outcomes, respect, voice, unbiased decision-making and trustworthy motives — and discussed how these expectations can be abandoned in the presence of bias.

For an example, he cited the verdict that a ChatGPT AI system made on the presence of implicit bias on a lawyer. It had written that the impact could manifest in “various ways,” including “influencing their decisions about hiring mentoring, promoting or evaluating other lawyers or staff,” “affecting their interactions with clients, witnesses, judges, jurors, or opposing counsel” and “leading to unethical or unprofessional conduct, such as discrimination, harassment, or incivility.”

The conversation integrated statistical evidence of the issues being discussed, including a table breaking down the disparity of bonds in Connecticut, which broke down felony and misdemeanor charges by racial categories of “Non-Hispanic Black,” “Hispanic” and “Non-Hispanic White.” For felonies, the racial gap between average bond postings yielded a bigger than $30,000 difference between the highest and lowest charged ethnic groups.

Robinson cited the 2019 federal Supreme Court case Flowers v. Mississippi, in which judges made a trend of dismissing Black jurors in cases with Black defendants out of fear of bias.

“I wonder if they would have struck white jurors if the defendant was white,” Robinson said.

Robinson drew the presence of bias into a personal level for the audience, highlighting the implicit assumptions made on each individual person with which you come across. He said that “when you see me, you see 10% of who I am” but the remaining 90% is not so visible.