A long, tangled history of the hospitality giant Sodexo

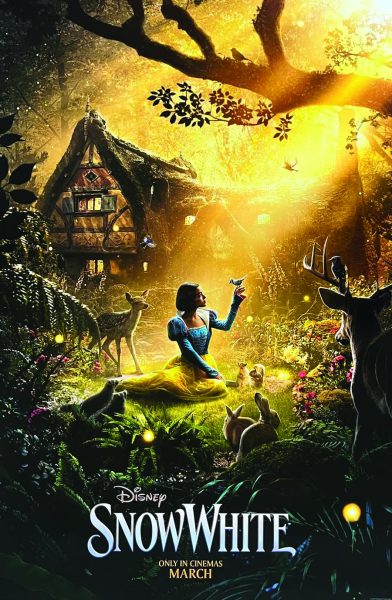

Photo courtesy of Jenelle Johnson

A display of food served in the Marketplace, West Haven.

In 1966, Pierre Bellon founded Sodexo in Marseille, France. 55 years later, the French food and facilities management company has an annual revenue of €22 billion, or about $25 billion. Sodexo’s services currently encompass 10 industries, including defense, government, healthcare and education.

Sodexo in the U.S. is most common on college and university campuses. A corporation this large is bound to have controversy riddled throughout its history, though much of this has not garnered much attention.

On Sept. 1, I began what I assumed would be a simple investigative piece into Sodexo’s presence at the University of New Haven. Nearly two months and 33 emails later, I have gathered almost every bit of information I sought to find.

Sodexo currently operates five prisons in the U.K. and one in Australia. They also provide services for correctional facilities in 84 prisons across mainland Europe and Chile, ranging from maintenance to food service and work training. They also appear to have policies that include a ban on working with anything other than democratically-elected governments, not providing services in countries with capital punishment (e.g., the U.S.) and not supporting tougher prison sentencing or other political agendas.

This sounds like an excellent policy. However, Sodexo’s claims of “receiving favorable results” during independently conducted inspections are countered by reports of abuse inside their U.K. prisons. An article in The Independent reported that inmate Natasha Chin was found unresponsive in her cell in 2016 at the Sodexo-operated prison HMP Bronzefield; her death was attributed to “medical neglect” on the coroner’s report.

In 2021, at HMP Peterborough, female prisoners reported having inadequate access to menstrual care products and other sanitary items. In 2017, four HMP Peterborough inmates were unlawfully strip-searched.

Companies, such as Marriott International, and private individuals’ lawsuits against Sodexo allege discriminatory lawsuits and mistreatment of employees. Since 2000, Good Jobs First, a subsidy and work violation tracker, reported over $103 million has been paid in penalties by Sodexo.

In 2002, Wood Dining Services (the former food provider for the university) was bought out by Sodexo. George Synodi, vice president of finance and administration at the university, told me: “The university has considered other food services, [but] the prices are about the same and buying food from the same suppliers and buying from the same regional labor pool.”

He emphasized the importance of management in university dining by saying that good management influences the quality and effectiveness of dining.

After reading about horse DNA being found in frozen beef used by Sodexo in Scotland, I asked Sodexo why students at the university should trust dining services to provide high-quality and healthy food. Sodexo said that “rigorous United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) guidelines and inspection procedures do not allow for horse meat to be imported or processed for human consumption.”

The term “local” was tossed around a lot in conversations with Synodi and other Sodexo management. I asked Sodexo to define the word “local,” an ambiguous word, and if there was a list of providers where they source food available. The answer remained the same: “We currently source produce locally and, whenever possible, we source items that are in season and available from local farmers and food producers.”

An interesting component of this response was their statement that they “[host] local farmers and producers on campus to provide students, staff and faculty the opportunity to purchase their goods and services.”

The last “farmer’s market” held by dining services at the university was the reselling of Driscoll’s berries, most of which are grown in California and Mexico and picked by workers earning $1.90 an hour, according to a lawsuit filed by Central Coast United for a Sustainable Economy against the California Agricultural Labor Relations board on behalf of undocumented migrant workers. Driscoll’s ethics are outside of Sodexo’s reach, but reselling another corporation’s strawberries and blueberries is hardly a farmer’s market.

The New Haven Independent reported that a sous chef at the university tested positive for COVID-19 in October 2020. A Sodexo spokesperson said that all safety measures were taken and “no one in the dining staff was negatively affected by [the chef’s] condition.” In contrast, the sous chef told the New Haven Independent that when he alerted Sodexo management, they “shrugged it off.”

Their health citations extend beyond this COVID-19 incident. In April 2021, a Sodexo spokesperson told me they had received a grade of 90 out of 100 on their last university health inspection, and “Extremely minor infractions were cited and fixed immediately onsite.” Requests for documentation on the inspection were not answered.

The issue lies in the hypocrisy of universities and other institutions. The university has written articles on its evolving faculty, hosted speakers and made declarations of being against mass incarceration, while sourcing food from a corporation that operates correctional facilities.

For universities to consider themselves forward-thinking, they must consider all components of their operation. This changing world does not, and should not, allow for discrimination, mistreatment, lack of transparency and violations by any entity. Students and employees deserve better, as does every other individual under the ever-expanding Sodexo.

Lindsay Giovannone is a senior majoring in history and minoring in criminal justice. She has been part of the paper since she was a freshman and has previously...