Linda McMahon, the newly appointed education secretary, informed Connecticut education administrators that their window to spend Elementary & Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER) resources had been closed earlier than previously expected. Administrators were surprised by the announcement, quickly working to identify the frozen funds and affected districts. This decision came only days after Pres. Donald Trump’s administration reclaimed $155 million in public health aid from Connecticut.

Gov. Ned Lamont voiced his dissatisfaction with the decision and said, “We are disappointed by the U.S. Department of Education’s decision to reverse their previously approved extension for the use of … ESSER funds.”

“These resources were designated to support the continued academic and mental health recovery of our students,” Lamont said. “The Conn. State Dep. of Education is actively engaging with federal partners and following all available procedures to seek project-specific extensions. We remain committed to doing everything we can to ensure that our districts and students receive the support they were promised.”

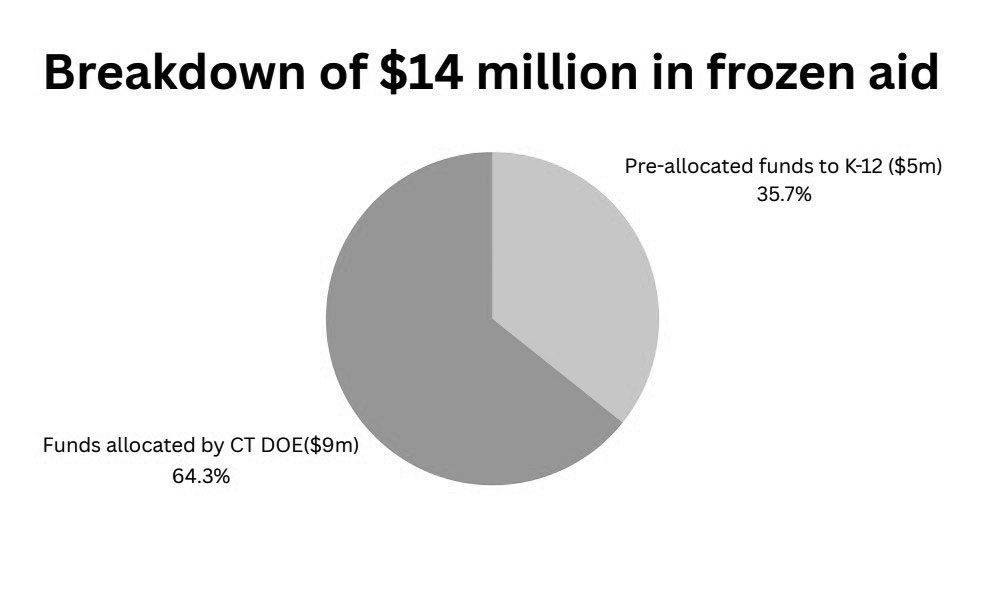

In February, the U.S. Dep. of Education permitted Connecticut to spend ESSER funds through late March 2026. The funds amount to roughly $14 million meant for academic and other programs in Conn. schools. It includes five million dollars already allocated to 21 K-12 districts as well as nine million dollars overseen by Connecticut’s Department of Education to be used to support local programs. This resource was created in 2020 and expanded in 2021 to address learning losses created by the 2020 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, and help underfunded districts create and maintain enriching after school and summer programs. Connecticut has received $1.7 billion in ESSER funds that have largely been spent.

According to McMahon, states are allowed to appeal to the Trump administration on an individual basis to spend more funds. This gives the administration full power over which projects they believe have merit. Though, it seems that McMahon has not offered guidance to administrators or specified the criteria that would be used by the administration to evaluate future funding requests.

Fran Rabinowitz, executive director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents and a former superintendent in Bridgeport and Hamden, has spoken about the reality of the situation schools are facing due to the aid freeze. According to Rabinowitz, almost all municipal school boards have submitted their budget requests to their local finance board or town council, meaning they are moving forward and planning under the impression that the funds were coming. The 21 districts that are reliant on relief awards that have now been frozen will not be the only ones affected. Communities that rely on assistance from the state to fund remedial assistance programs, which are used to reteach basic skills like math and reading to address learning gaps, and tutoring will feel the effects of the freeze as Connecticut was paying for these programs with ESSER funds.

“The clawback of funds by the U.S. Department of Education is an alarming move that will directly impact students, families, and educators — particularly those in Connecticut’s highest-need communities,” said Lisa Hammersley, executive director of the School and State Finance Project. “Students need stability and consistency to thrive in school and excel academically. This about-face from the department continues to upend that stability, undermines local budgeting and raises significant concerns about the future and availability of federal education funding.”

Charlene M. Russel-Tucker, Connecticut’s education commissioner, has indicated her department’s mission to seek more information on the freeze and advocate for “each and every” project that had been approved previously. Lamont and leaders of the General Assembly’s Democratic majority have vowed to not wait until summer or fall to begin considering replacing parts of the federal aid cuts and freezes with state funding.