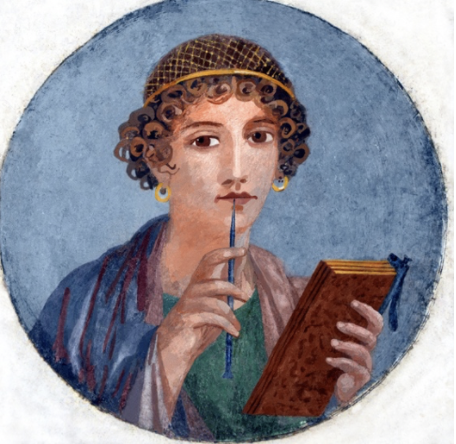

Sappho: Poetic antiquity in modern times

“I tell you/someone will remember us/in the future.”

Truer words have not been written, as Sappho is remembered for her literary innovation and contribution to the LGBTQ+ community thousands of years after her lifetime. What is known about Sappho, much like most ancient history, has been pieced together using salvaged portions of her own transcripts, ancient documents and the descriptions and opinions of her better-documented contemporaries.

Although the Greek poet and lyricist wrote about many topics including marriage, virginity and the Greek heroes and gods, she is best known for Sapphic Poetry, which is partly defined by a unique meter and line construction and vowel-laden language.It is more prolifically known by its subject: same-sex female attraction and ardor.

One poem reads, “I would much prefer to see the lovely / way she walks and the radiant glance of her face / than the war-chariots of the Lydians or / their footsoldiers in arms.”

It is from Sappho and her art that the term “lesbian” is derived to mean a woman who is exclusively attracted to other women. Born on the Greek island of Lesbos in 620 BCE, she was a renowned poet, likened in ability to Homer and named the “tenth muse” by Plato. Despite her skill and writing ability, she was criticized by her contemporaries because of her deviation from the classic form of poetry, which was meant to tell a story and communicate information eloquently. Instead, Sappho wrote poetry that was expressive and communicated her own emotions and experiences, commonly erotic in nature.

A central focus of Sappho’s work was conflicts regarding love. As she writes of female beauty and attraction confidently – “toward you beautiful girls my thoughts never alter” – she also expresses the difficulty in finding enduring love with a woman in her poetry.

In one poem, she marvels at the godliness of a man with whom the woman of her affection is taken.

In another piece, she pleads with the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite, to bring her love, to which the goddess says, “Whom this time should I persuade to lead you back again to her love? Who now, /oh Sappho, who wrongs you?/If she flees you now, she will soon pursue you;/ if she won’t accept what you give, she’ll give it;/ if she doesn’t love you, she’ll love you soon now, /even unwilling”

Sappho’s writings are relatable beyond simplistic attraction. She also wrestles with the topic of virginity. While it is difficult to categorize where it is derived from, she expresses a definite conflict in understanding virginity, at one point writing in a call and answer format, “Virginity, virginity, where have you gone and left me?/ Never again will I come to you, never again.”

As a social construct, virginity is modernly defined in a multitude of ways and is largely individualized. The understanding of virginity is widely discussed in the LGBTQ+ community, as the traditional understanding of sex as vaginal penetration by a penis is not accurate for many relationships. As a poet preoccupied with same-sex attraction, it is not surprising that Sappho took part in similar conversations in her art by discussing the definition of virginity and the permanence of the construct.

Beyond the definition of virginity, Sappho may have also been exploring the stigma of virginity. In a fragment attributed to her, she writes, “Do I really still long for virginity?” Clearly, she questioned how important virginity, as she understands it, is to her.

Such writings coupled with her interest in marriages and the Greek goddesses Aphrodite and goddess of marriage Hera suggest that she may have had strong opinions on how virginity operated in her society and her own relationships.

From her unorthodox evolution of poetry to the modernity of the topics her poetry covered, Sappho remains a relevant and prominent woman in society to this day. Her work exemplifies the potential power of one singular voice, however emotion-filled it may be, to reach an unfathomably large audience, resulting in an unquantifiable impact.

Isabelle Hajek is a senior at the University of New Haven majoring in psychology with a concentration in forensics and a double minor in criminal justice...