Language matters, especially when it was here first

“A language is not just words. It’s a culture, a tradition, a unification of a community, a whole history that creates what a community is. It’s all embodied in a language,” said philosopher and father of modern linguistics Noam Chomsky in “We still live here – âs nutayuneân,” a 2011 documentary on the Wampanoag people’s journey to reclaim and revive their language.

If language is culture, then the English language, used as a tool to imperialize, colonize and genocide full populations of Native Americans is telling in its co-optation and perversion of Native American language.

Interactions between the Wampanoag people and Europeans were brutal. Members of the Wampanoag culture were murdered, stolen from and colonized. Although the same thing has happened repeatedly with other indigenous populations, the Wampanoag were the first in North America to experience it.

First, their population was decimated by disease by the first wave of English slave owners overtaking their shores. Then in 1620, the Wampanoags made the strategic decision to aid the newly-arrived pilgrims by teaching them agricultural practices that would sustain them in trade for alliance, which was needed after two thirds of their population was killed.

This decision was followed by a long colonial history of withstanding legislation that was meant to destroy native populations. At the core of this legislative scheme was the destruction of native culture, largely through the methodical prohibition of native dialects.

The cultural importance of language, and subsequent national strength, is so important that in working to conquer native peoples, the U.S. spent the modern equivalent of $2.81 billion to fund boarding schools whose purpose was to Americanize native children to speak English and practice Christianity.

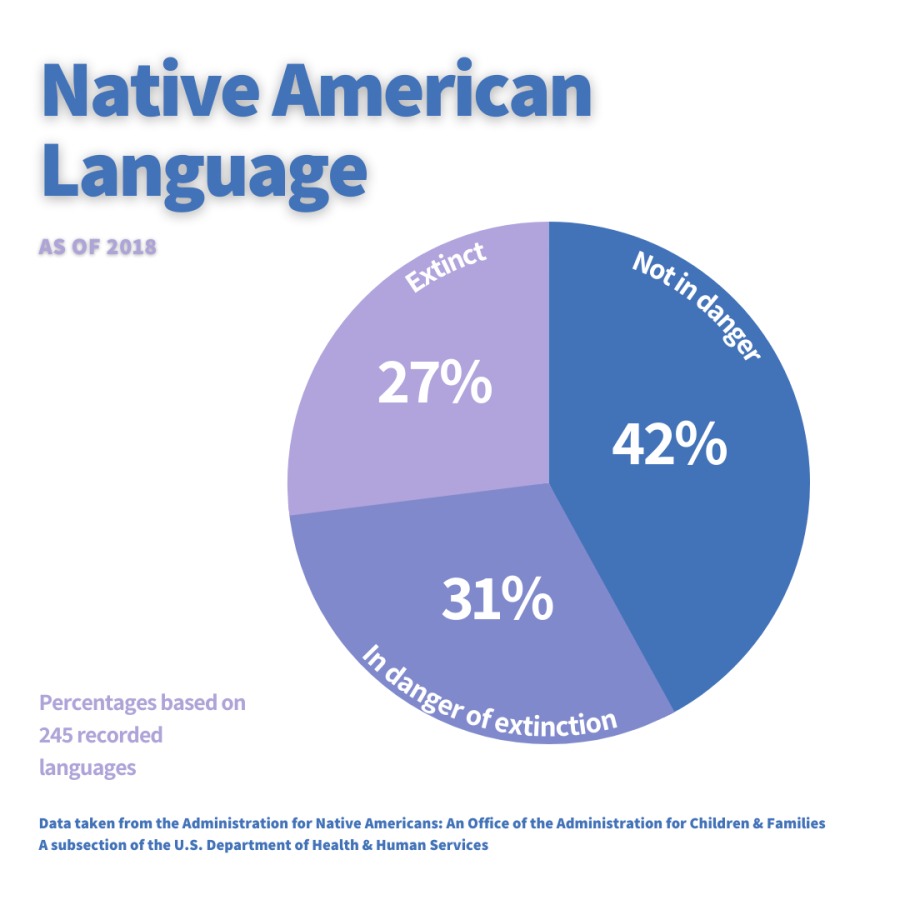

A 2018 article released by The Administration for Native Americans said that of the 245 recorded indigenous languages, 65 were extinct and 75 were in danger of extinction. This has led to a native language revitalization effort in recent years.

What has been saved of native languages is commonly misused or perverted by English speakers, so much so that it is ingrained in the English lexicon without much conscious thought from speakers.

The most obvious, but overlooked example, is the use of the word “Indian” to describe indigenous Americans. First coined because Christopher Columbus thought that he had found the people of the West Indies, the word has continuously been misused. It has expanded to other terms such as “indian-giver,” “indian summer” and “and indian burn”—all similarly misappropriating the term harmfully.

Although controversially discussed, the word “chief,” used to denote senior positions in companies such as Editor-in-Chief, Chief Executive Officer and, ironically, Chief Diversity Officer, is another instance of misused language. While each native population had their own term for their leaders, upon European colonization of the region, each leader was generalized to the term “chief” derived from the French language.

Some indigenous people reject the term, while others have accepted and chose to revere it. In either perspective, whether a term of disrespect or reverence, chief is a term used by the English language to effectively homogenize all indigenous people as one, and to reappropriate it in the English language is to further degenerate native culture by either perpetuating disrespectful language or stripping away the dignity of the title by so liberally bequeathing it.

The piéce de resistance of the co-optation of native language is the renaming of prolific Native Americans. There is a mainstream understanding of their original names, yet from history lessons to Thanksgiving articles the Westernized monikers continue to be used.

It’s not Geronimo. It’s Goyathlay of the Bedonkohe Apache. It’s not King Philip. It’s Metacomet of the Wampanoag. It’s not Joseph Brant. It’s Thayendanegea of the Kanien’kehá:ka. It’s not Chief Joseph. It’s Heinmot Tooyalakekt of the Nez Perce.

Names are important. They’re an identity, a cultural ode, so learn them. Learn theirs.

Isabelle Hajek is a senior at the University of New Haven majoring in psychology with a concentration in forensics and a double minor in criminal justice...