Indigenous Peoples’ Day highlights perseverance and awareness

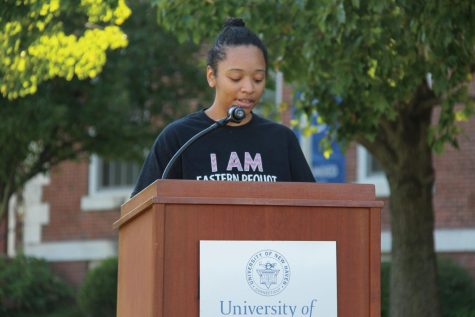

Photo courtesy of Charger Bulletin/Amber Cholewa.

University professor Michele Berman stands on Maxcy Quad during Indigenous Peoples’ Day ceremony, West Haven, Oct. 10, 2022.

Oct. 10 marks Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and university members gathered on the Maxcy Quad this year to highlight voices within the community that sought to educate others on the power and passion that they hold on this national day.

Dean of Students Ophelie Rowe-Allen gave opening remarks, and discussed the value of the land on which the university sits. This served as a catalyst for Senior Associate Dean of Students Ric Baker to then read the university’s land acknowledgement statement.

Baker said “land is sacred to all of us whether we consciously appreciate it or not” and that it is constantly changing to provide resources and lessons to those who use it.

In the statement, Baker said “The University of New Haven acknowledges the painful history of genocide around the globe–for native, aboriginal and Indigenous peoples. We honor the multitude of diverse tribes and nations who were forcefully removed from, and those still connected to a land that was pillaged and stolen under a tyranny of colonialism.”

“Indigenous Peoples’ Day draws attention to the pain, trauma and broken promises that were erased by the celebration of Columbus Day,” Rowe-Allen said before making way for Indigenous voices within the community. “Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebrates, recognizes and honors beautiful traditions and culture of the Indigenous people, not just in America, but around the world.”

Destiny Ray is a cybersecurity and networks major and is both the treasurer of PRIDE and a diversity wellness educator. She spoke at the ceremony to represent the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation. She spoke on the impacts of colonialism and the history of her tribe.

Ray explained that during the 1637 Massacre on the Long Island Sound near Mystic, Conn., 300-700 of their people were killed by the colonists, either by being burned alive or by sword, in order to acquire resources from the tribe’s land. She then proceeded to discuss their new settlements and their relationship with the state to maintain their basic needs, until financial ideals revoked their assistance.

“Our fight to get federal recognition started in 1978 with the letter of intent to go through the BIA [Business Impact Analysis] process. We were number 35,” she said. “Five years later, our cousins, the Western Pequots, received federal recognition.”

“Our tribe would build our case for the next 20 years for federal acknowledgement, and pay millions of dollars collecting documents and doing research,” she said.

In June of 2002, the Eastern Pequots gained federal recognition, which did not last long as many towns in the county requested it be revoked. Ray said that there were attempts to appeal the determination of the recognition.

“It’s been two decades since we’ve had federal recognition, and we don’t want another decade to pass without it,” Ray said. “It’s import

ant for everyone listening to educate themselves, and if you have the opportunity to help a tribe, do it.”

Her father, Mitchell Ray, is the chairman of the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, and spoke after his daughter that afternoon. He added onto the context provided by Ray, in further discussing the 1637 Mystic Massacre which divided the Pequot people into Eastern and Western tribes.

In the 1650s, the Eastern Pequots were taken to one of the first reservations in the country, in response to mistreatment by the Mohegans, he explained. He also discussed how his tribe wandered for multiple decades before settling. Once they did, overseers from the government ensured their care, which was then transferred from the wellness department to the parks department.

“By 1978 the federal government decided to start the federal acknowledgment process to help settle land claims between the Native Americans and the federal government, and also to start the relationship from government to government,” Ray said. He said the documentation of their lineage, culture and means of survival spanned across thousands of documents during the two-decade span discussed by his daughter.

Columbus Day in 2005 was when their federal acknowledgement was reconsidered.

“We’re trying to make wrongs right, but we can’t do it without your help,” he said at the end of his speech, again calling the crowd to action. He asked for people to petition to demand that their tribe uphold their federal acknowledgement. A letter of support can be found on their website.

Angelina Caroli, a senior criminal justice major, is another student whose voice was heard on Indiginous Peoples’ Day. She spoke in representation of her tribe, the Mohegan tribe.

The event was called “a step in the right direction for Indigenous recognition” as Caroli said that “Indigenous people are not often recognized in media unless it’s in a negative light.”

“Indigenous people are not your mascot, your Halloween costume or caricature that puts on a show for you. We are human and we are still here,” Caroli said in light of the necessary increase in visibility for the population.

“Educate yourself and support Indigenous issues, and remove harmful stereotypes and Indeginous racial language from your lexicon,” was another call-to-action cast into the audience.

Michele Berman, chemistry lab manager at the university, stood before the crowd to discuss her long connections to her culture and the experiences that stemmed from such. She is a descendant of a number of the original families who immigrated to Canada.

“Canada had interest in census laws that complicate Indigenous genealogy tracing,” she said. “I may be Mohawk, but I am unable to prove that.” She voiced value in the connections she made with people from different groups that welcomed her into their activities.

“I heard the singing, I saw the dancing, I saw the generosity and knew I had to understand and learn,” she said, reflecting on the 46 years of powwows that she has attended.

Her means of culture and expression through dress were taught to her by the people that she met at these events. She said that the Wampanoag dressed her in Indigenous clothing for the first time. “My first dance outfit was a Southern Plains traditional plath outfit,” she said, “Because that’s what my friends knew, and that’s what they taught me.”

Berman discussed the beadwork that she was wearing to the ceremony, which was handed down to her. She said that the hair ties she wore were over a thousand years old. “Why did I get them? Why did they think this much of me? I’m really proud of them.”

Mary Lippa, the vice president of community, advocacy and diversity for the Undergraduate Student Government Association, spoke on behalf of the work being done at the university to work towards recognition in the university setting.

“I want to first acknowledge the harm perpetrated by the celebration of Columbus Day on a local, national and personal level. Our school has a long way to go in recognizing and honoring indigenous cultures, particularly the ones around us. This is a good first step for us, and I hope to see the momentum continue,” Lippa said.

In regards to a current major project in this direction, Lippa said “USGA is working in tandem with administration to develop a land plaque to place on campus so that the true ownership and history of the land cannot be denied.”

The new Director of the Myatt Center, Khristian Kemp-Delisser, also gave their first speech at the university at the end of the event. They referenced Sherman Alexie, an Indigenous writer, and discussed the power of understanding the landscape and land acknowledgement.

Mia Adduci is a senior studying communication concentrating in multi-platform journalism and media who began writing for the paper her first semester on...