To be wrongfully convicted: Students given an anecdotal lens into the justice system

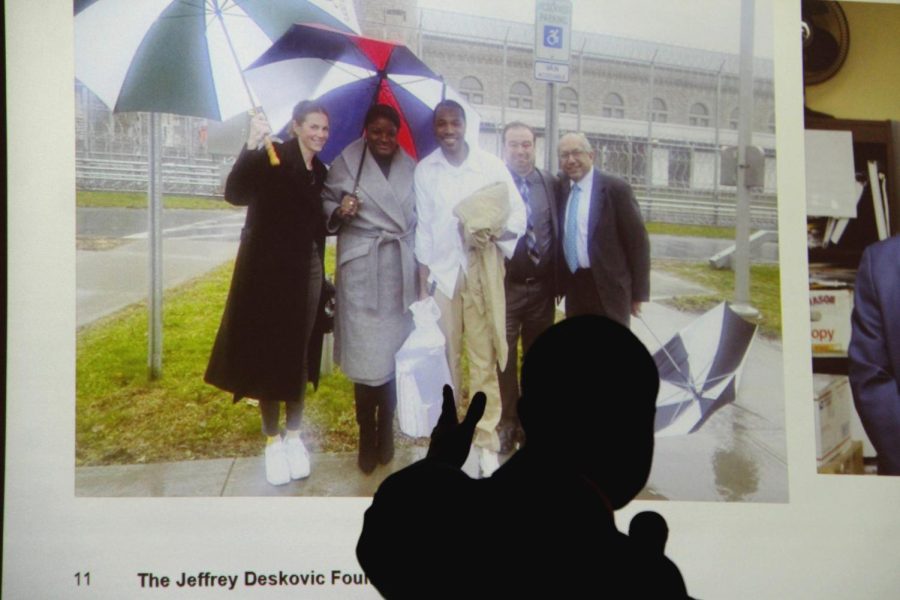

Photo courtesy of Charger Bulletin/Alida Bates.

Andre Brown points to images of after his release.

“An individual encapsulated in quicksand; breathing out of a straw, and the only ones giving him oxygen are his family, friends and at times, birds and other creations of God through faith –– that is what incarceration is like.” Andre Brown was in accompaniment of Jeffrey Deskovic last night following an invitation from the Forensic Science Student Association. The pair placed themselves in front of a room full of forensics staff and students to recount their experiences with false incarceration in the American criminal justice system.

Deskovic and Brown are two of the 3388 people who have been incarcerated in the United States from 1989 into the present day.

Deskovic spent 15 years in prison after being convicted of first degree rape and second degree murder. His 16-year-old mugshots sat on the large screen at the front of the room as he recounted his experiences. This surrounded the criminal justice system that responded to the murder of his classmate, who notably was just one year younger than he.

Deskovic fit the criteria established within the New York Police Department’s psychological profile for the perpetrator of the incident –– a list of boxes which he said were incredibly vague and not assistive.

The law enforcement officials handling the case asked him to undergo a polygraph test, kickstarting what he described as “psychological manipulation” from the Peekskill Police Department.

Deskovic recounted that he was not read his rights, nor did he enter the polygraph test with an understanding of how it worked. At 16-years-old with a prior interest in a career as a cop, being told that this task would assist the police made the need for understanding obsolete.

The official administering the test “launched into his third-degree tactics,” which he said included “invad[ing] my personal space, rais[ing] his voice at me; he kept asking me the same questions over and over again” for upwards of six and a half hours.

Toward the end of the test, Deskovic recalls hearing “What do you mean you didn’t do it? You just told me through the polygraph test result that you did it. We just want you to verbally confirm it.” He was told that a confession would allow him to go home.

“I wasn’t thinking about the long-term, I was just thinking about my safety in the moment,” Deskovic said.

There were no video or audio recordings of this polygraph, or any evidence beyond police verdicts. He said that in court, these verdicts omitted the threats and false promises placed upon him in the interrogation room.

Deskovic continued to recount his courtroom experiences, telling the audience that the medical examiner investigating the case had claimed that the victim was “promiscuous” and used such as an explanation of why the DNA obtained from her autopsy did not match his.

He went as far as opening up about an argument that was made that he felt was “burned” into his mind. There was one line in particular that stuck with Deskovic: “negative DNA test result is no insolation to a guilty verdict.”

Deskovic directed a number of his takeaways towards the student population, providing advice and reminders to those entering fields that interact with the criminal justice system. He said that “experts should always be subjected to questions about the methods they use in order to arrive at their opinion.”

It was in 2006 that Deskovic’s case was picked up by the Innocence Project, and in that same year, his case was turned around.

Despite his false conviction being the reason he was placed in jail, Deskovic spoke on the level of stigma he experienced reentering the free world, in which people question the impact of being surrounded by criminals, leading to distrust.

Regardless of these stigmas, Deskovic went on to receive multiple higher level degrees, with his latest feat being a graduation from law school, which has catalyzed him in a direction to pursue a career as an attorney. This led him to create the Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice.

One of his clients was Brown, who spent 23 years incarcerated. He has only been out of prison for approximately 80 days at the time of his New Haven visit.

Brown was convicted on account of a shooting which involved two victims in the Bronx, New York.

He said that he was “screaming at the top of my lungs, ‘you guys know I had nothing to do with this:’ my voice went unheard.”

He recounted his experiences of having to get medical professionals involved in his trial, explaining how he was accused of a crime which would have required him to be able to run at a level that was not physically possible following his medical conditions –– he had a surgeon on the stand to attest to this.

“As we can see, there’s many empty seats here,” he said.“Nobody cares, and it’s heart wrenching, until you have advocates come on board.” This worked as a segway into a large motif of his dialogue that evening, one which urged those in the audience to speak out against observations of injustice.

Brown also said that “Lady Justice is blind but she has the ears to hear the cries of the people, and you are the people.”

Further pursuing his call to action, Brown said that “your voices are command as prominent members of society.”

Deskovic spoke on the necessity of raising money to help free more people, in light of another individual being found not guilty this week. This amounts to a total of 13 exonerated people having cases reevaluated to confirm innocence. “It’s about trying to raise money to get more people home that are wrongfully convicted,” he said. The event in the German Club raised $283 towards the Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice.

In closing, Deskovic said that “where the evidence leads you is where you’re supposed to end up, as opposed to the tunnel vision; as opposed to working backwards; as opposed to ignoring evidence.”

It can be noted that a set of University of New Haven professors had involvement in Deskovic’s case. This includes lecturer Ted Schwartz, who was involved in the reevaluation of the evidence at hand, and associate professor David San Pietro, who held a role in the post testing of the case.

Mia Adduci is a senior studying communication concentrating in multi-platform journalism and media who began writing for the paper her first semester on...